When Abass Daud was a child, there were no schools. There was only war. The government in Khartoum was waging war on his homeland in the Nuba Mountains, located in Sudan’s South Kordofan region near that country’s border with what is today South Sudan.

“We were always running from the bombs of the Antonovs and the bullets of the soldiers. And the army would look for us when we were hiding. But in 2002, there was a ceasefire, and I was sent to school,” he said.

“It was exciting. I had a voice inside me telling me that I had to go to school. Many of us young boys went. I had no shoes nor proper clothes, but we’d walk very early in the morning to the school.”

By 2009, attacks from the north had started again, and his school closed. He fled to Gidel, which was a bit safer, where he finished his primary school and began secondary school. He earned money for his school fees by working part-time for Arab families, cleaning floors, washing laundry and working on their farms.

In 2011, the war intensified, and all schools closed.

“Many people flew out of the Nuba Mountains, especially those who were better off, who had money. Since I came from a very poor family, I went home to my family to wait with them for whatever would happen,” he said.

The following year, word came that a refugee camp had formed near Yida, on the other side of the border with South Sudan. Daud joined with other boys and girls from his village and trekked there on foot.

“When we got to Yida, we searched for the school. But it was a new camp and not well established. We found it, but there were 150 students in a class. And there wasn’t much food because the roads were bad. So hunger was a problem. I eventually decided to go back to the Nuba Mountains,” he said.

Daud only had 250 South Sudanese Pounds when he got back to his family’s home. So he borrowed a bicycle from a friend and started riding several days across the border to Bentieu, where he would buy sugar and coffee and bring them home to sell. By 2013, some schools reopened and he had saved enough to pay the fees. There was near constant bombardment, so any significant noise caused the students to run for the trenches they had dug around the school grounds.

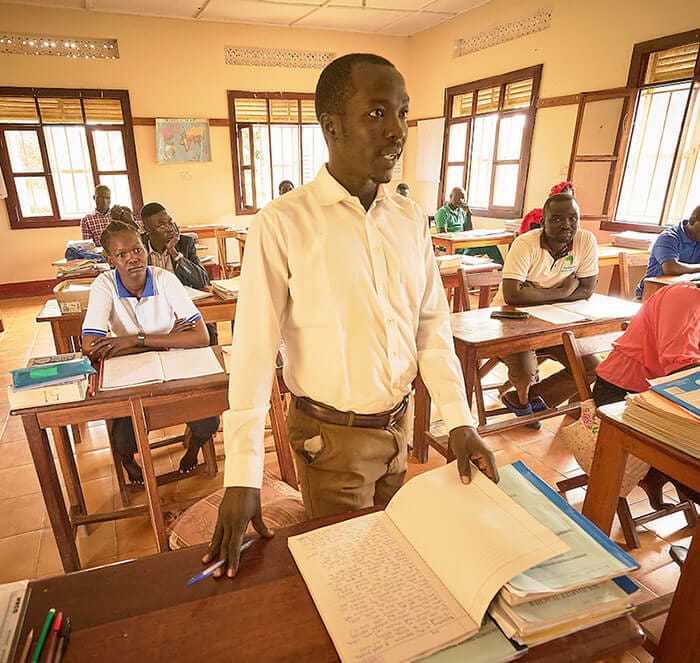

Daud finally was offered a chance to evacuate to the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, where he finished secondary studies and passed his graduation exam. He returned home and worked as a volunteer teacher for two years. He wanted to do further studies in education, however, so his priest finally nominated him to go study at the Solidarity Teacher Training College in Yambio.

He says the college marked his first exposure to South Sudanese, but he got along well with his classmates. Speaking English, he says, leveled the playing field in a community with people from many ethnic backgrounds. And he praises how the school brought together people from around the world.

“We have teachers who come from different countries, from different continents. They’ve come a long ways simply out of their love for us. They have seen our suffering, and they’ve sacrificed their time and their lives to come and share our situation, and to help us have knowledge that we can spread to other people,” he said.

Although his studies were temporarily interrupted because of Covid, Daud graduated from STTC in October and returned to the Nuba Mountains.

After years of overcoming obstacles, he was ready to teach.

“At first I had wanted to be a doctor, because there was so much fighting and when people were injured there was no one to care for them. But I also saw how during the war all the foreign teachers left. Only the native teachers remained, and they didn’t have enough knowledge. So I decided to be a teacher in my own land, so I can help my people who are suffering,” he said.

“If we can have trained teachers, they will change the minds of young children, and the generations to come will look for alternatives to fighting. They’ll learn to resolve their conflicts and live in peace. I became a teacher in order to share the message that war isn’t the solution to our problems, that dialogue can be a means to resolve things. In the Nuba Mountains, teachers are important for the future.”

Above: Abass Daud Idriss speaks during a class at the Solidarity Teacher Training College in Yambio, South Sudan.

Story and photo by Paul Jeffrey