Solidarity with South Sudan is an international network of Catholic groups that trains teachers, health workers and pastoral agents in Africa’s newest country. In the process, its members seek to model collaboration that brings together people from disparate backgrounds in pursuit of a common mission.

“All religious congregations are facing a crisis of vocations, so they have to network with others. Solidarity was founded to bring together people from different congregations, and in this community that has been excellent,” said Brother Christopher Soosai, a De La Salle brother from India who serves as principal of the Solidarity Teacher Training College in Yambio.

“We have a common mission and a common life together. That brings richness and variety. We are different in our ages, tastes, and backgrounds. We are different races, come from different countries, and speak different languages. But that’s the beauty of difference when you come together for a common task.”

Students pose with Brother Christopher Soosai, a De La Salle brother from India, at the Solidarity Teacher Training College in Yambio. To bridge cultural gaps, students intentionally learn the songs and dances of the tribes of other students. Brother Chris is the school’s principal.

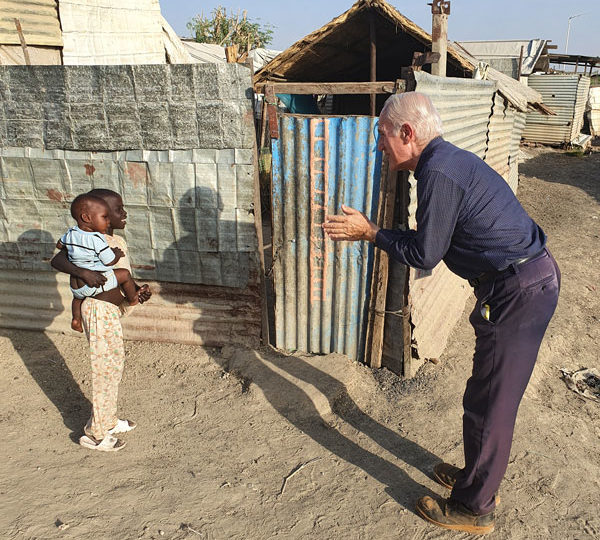

In Africa, such cooperation between Catholic orders is almost unheard of, according to Sylvanus Victor Okon, a Marist brother from Nigeria who teaches at the Yambio college.

“To live in a mixed community has been an amazing experience for me. This was something unthinkable in Africa, that sisters and brothers could live together in the same community. If you talk about this in my country, people ask, ‘How is that possible?’ I’ve had to learn about how to interact with people from other cultures. It’s helped me to understand that we are one, humanity is one, and that we’re not that different from one another. We all have the same goal of loving God and working for God,” he said.

“I’m blessed in the midst of these great men and women. Almost all of them are former provincials or leaders of their congregations, and I am the least in terms of my experience of religious life and in terms of age. I’m like the Benjamin of their house. Yet they accept me as one of them. There’s no segregation, no racism, no tribalism, no ethnicity. We are one. There’s no Jew nor Greek in this house.”

Besides serving as a model for the church’s mission, Brother Sylvanus says Solidarity’s common life presents a hopeful ideal for war-torn South Sudan.

“Solidarity is a microcosm of what’s supposed to happen in South Sudan, where all the tribes are supposed to come together, no longer Dinka or Nuer or Azande, but everyone working as one. That’s what we’re trying to do in Solidarity with South Sudan, and it begins in our house. Here you see people from all the continents of the world. And when we go into the community, we see all the tribes of South Sudan coming together in the schools, living together in peace, in love and unity, trying to develop their country. That’s what we’re trying to instill here in the school.”

It hasn’t been easy.

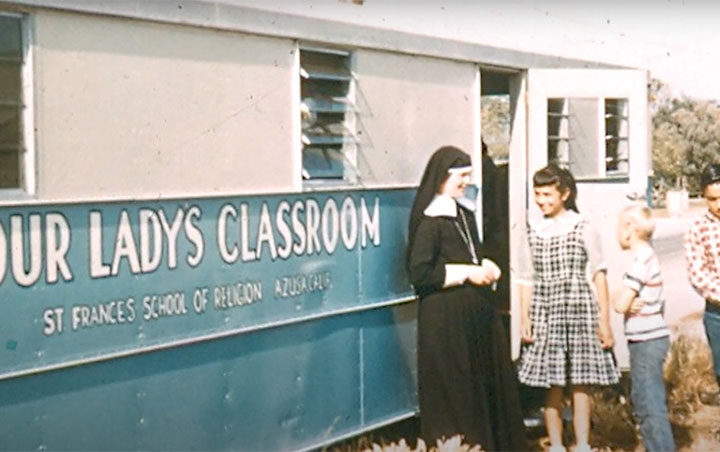

Maria Martinelli was one of the first members of Solidarity with South Sudan. She’s an Italian physician and Comboni missionary sister who came to South Sudan in 2008 to launch a training center for nurses and midwives in Wau, the Catholic Health Training Institute.

“The idea was to give the same value to the work of men and women. Yet there are some prejudices that are still quite strong, however. The men, in particular the priests, they are…” she began, then paused.

“The sisters,” she eventually continued, “do much of the work but their point of view isn’t considered to be of equal importance. So the fact that men and women in Solidarity can work together and both have a voice, and their voices are equally valued, is a strong witness.”

Martinelli admits Solidarity’s ministry raised a few eyebrows among church leaders.

“The Solidarity model raised questions in some places. I remember one bishop who wouldn’t accept men and women staying together, because of cultural issues,” she said.

Martinelli, today the provincial for Comboni sisters in South Sudan, admits not everyone is cut out for community life based on equality.

“The men in the community can’t come expecting the women to be the cooks. They have to offer something also. As brothers and sisters, not as bosses and servants.”

Sister Rosa Le Thi Bong, a Vietnamese member of Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions, left Solidarity in 2021 after 14 years of living in the shared community in Riimenze.

“I felt enriched. We enjoyed learning from each other. We have different ways of prayer, of food, different ideas and ways of working. It was a challenge,” she said. “Sometimes people would cook our meals in the way of their culture. I still tried to eat it, even if I didn’t like it.”

Story and photos by Paul Jeffrey

Feature photo: Brother Sylvanus-Aniebiet Victor Okon, a Marist brother from Nigeria, dances with students at the Solidarity Teacher Training College. Brother Sylvanus is an instructor in the school.